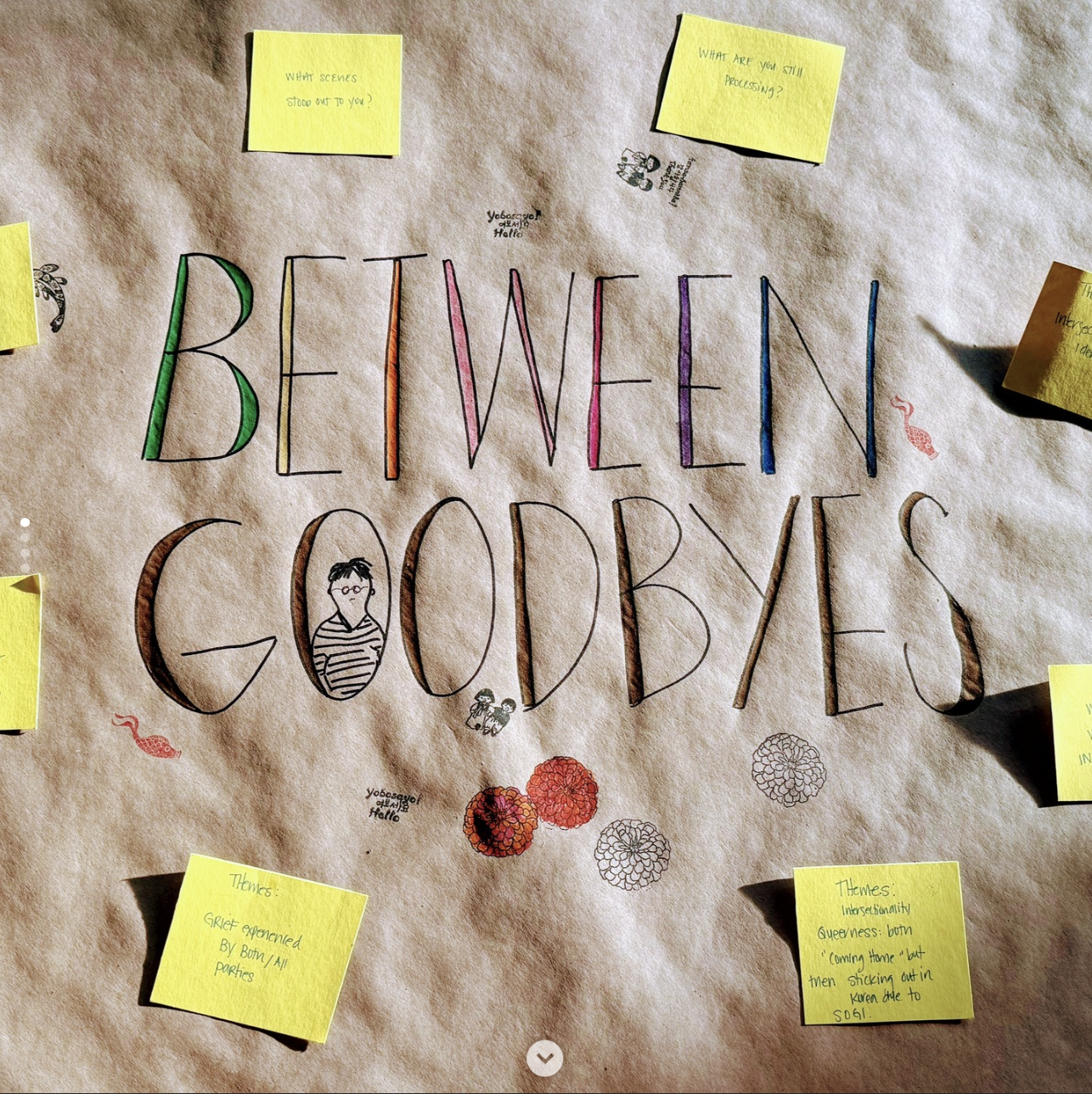

About the film

When a queer Korean adoptee visits her original mother in Seoul, long-held regrets and cultural misunderstandings come to the surface alongside tenderness, humor, and tenacity.

“No one supported our wanting to keep our children.”

—Anonymous Korean Birth parent §

Stranger Adoption vs. Kinship Adoption

Stranger adoption is very different from kinship adoption. Kinship means the new parental figures already knew the child as well as their original parents. The adoptee retains their identity and family history. Stranger adoption involves an exchange of money and the option to legally rewrite a child's name and family history (Further Reading: Strangers and Kin, Barbara Melosh).

“Why did she give up her child?”

“How could a mother do that?”

These are the most common questions we hear. Far fewer people ask, “Was this choice even made by her? What other choices did she have access to? Why did over 200,000 families relinquish their children, knowing they may never see them again?” This film was conceived out of our frustration with narratives of adoption that exclude Birth Family or Original Family voices and frame adoption as beginning with their guilty choice. We grew up being told that our Original Families relinquished their parental rights out of “love”, but we never heard about their desperation.

Traditionally, parental rights in South Korea only go to the father. If he died or filed for divorce, his children would remain under the control of his family members. Mothers would have no legal claim to their own children. Therefore child relinquishment was usually decided as a family and in many cases without a mothers consent. It wasn’t until 2005 that mothers were granted the same rights as fathers.

During the boom of international adoptions in the 1980s, South Korea was still under the rule of a military dictatorship. Draconian population control policies handed down from the United Nations were aimed at married women. Their goal was to drastically reduce birth rates from an average of six children to two and later, to one. Sending children overseas en masse coincided with a nationwide strategy of economic growth above all else. By avoiding the cost of caring for these children and turning them in revenue, the government made billions of dollars. The United States and western Europe created this industry and benefited the most from this arrangement.

We hope to be another voice in the critical discourse started by generations of Adoptees before us. In making this film we aim to re-educate the public and remove the stigma associated with being an original mother or parent.

Community centered

Although Between Goodbyes is a documentary that focuses on a Korean adoptee and her original family, the emotional core of the story is relatable for all types of adoptees and birth families. We hope the film and our community events can help build more bridges between all types of adoptees, original families, formerly fostered folks, and children of adoptees.

Learn More

- In Reunion: Transnational Korean Adoptees and the Communication of Family by Sara Docan-Morgan

- Adoptee Reunions: A Happy Ending Can Be Elusive by Katelyn Hemmeke

- Disrupting Kinship: Transnational Politics of Korean Adoption in the United States by Kimberly D. McKee, PhD

- Korean intercountry adoptees support birth mother’s rights in South Korea

- For adoptees who went through Korea Social Service (KSS) you can learn more about how to request the Korean version of your Adoptive Child Study Summary at www.paperslip.org

Sources

* Outsiders Within: Writing on Transracial Adoption Edited by Julia Chinyere Oparah, Sun Yung Shin, and Jane Jeong Trenka

† Child Adoptions: Trends and Policies - United Nations

‡ Adoption Network - "Adoption Facts." Adoption Research. 2013.

§ Adoption Wisdom by Mar